After a recent talk I had with my uncle on the future of education, he sent me this PatriotPost Founder’s Quote Daily:

"Without wishing to damp the ardor of curiosity or influence the freedom of inquiry, I will hazard a prediction that, after the most industrious and impartial researchers, the longest liver of you all will find no principles, institutions or systems of education more fit in general to be transmitted to your posterity than those you have received from your ancestors." --John Adams, 1798

|

When I did a Google search for the quotation, I was immediately struck by the patriotic pattern of sources and their political similarity to each other. However, no Adams papers or .gov sites popped up. Curious, I started to dig deeper into the context of the quotation.

John Adams initially delivered the passage in his address to the Young Men of Philadelphia on May 7, 1798. As a whole, the text reads as a benediction to the young men’s coming lives, wishing them luck and joy as they step off in their ventures (particularly, it seems, in defense of the country).

Years later, Adams reflects on his words to the young Philadelphians in a letter to Thomas Jefferson. In this 1813 letter, he celebrated the boys’ enthusiasm towards the American Revolution and his and Jefferson’s roles in that history. He goes on to note the unifying element of both the Constitutional Assembly and the group of young men was two-fold:

“the general principles of Christianity in which all those sects were united; and the GENERAL PRINCIPLES of English and American liberty, in which all these young men united, and which had united all parties in America, in majorities sufficient to assert and maintain her independence.”

Consider the balance he gives to the two sets of principles - religion unifies groups and liberty unites individuals, but it is their combination that constitutes American freedom.

If there was any doubt to the intentional nature of this balance, read his next words:

“Now I will avow, that I then believed, and now believe, that those general Principles of Christianity, are as eternal and immutable, as the Existence and Attributes of God; and that those Principles of Liberty, are as unalterable as human Nature and our terrestrial, mundane System.”

When aligning the tenets of religion and liberty in the same sentence, note the elegant use of the semi-colon to bond these foundation stones of Adams’ belief system.

With this in mind, it was fascinating to compare Adams’ letter to a typed version on a webpage from Constitution.org titled ‘American Independence was Achieved Upon the Principles of Christianity.’ By deliberately leaving out the principles of ‘English and American liberty,’ the title promotes a religious reading of Adams’ words. To further align with this guiding lens, consider the editing. The first paragraph of the page is the quotation about ancestors from the 1798 Philadelphia address, while the rest of the text is from the 1813 letter to Jefferson. However, no quotations, italics, etc. make this distinction clear. Without the appropriate contexts, this webpage insinuates that, based on the wisdom of ancestors, the entire Independence movement was a result of the forefathers’ religious beliefs.

What the Constitution.org website fails to include, as well as what the Patriot Post readers might not find out, is the next paragraph to Adams’ 1813 reflection:

I might have flattered myself that my sentiments were sufficiently known to have protected me against suspicions of narrow thoughts, contracted sentiments, bigoted, enthusiastic, or superstitious principles, civil, political, philosophical, or ecclesiastical. The first sentence of the preface to my defence of the constitution, vol. 1st, printed in 1787, is in these words: “The arts and sciences, in general, during the three or four last centuries, have had a regular course of progressive improvement. The inventions in mechanic arts, the discoveries in natural philosophy, navigation, and commerce, and the advancement of civilization and humanity, have occasioned changes in the condition of the world and the human character, which would have astonished the most refined nations of antiquity,” &c. I will quote no farther; but request you to read again that whole page, and then say whether the writer of it could be suspected of recommending to youth “to look backward instead of forward” for instruction and improvement. [emphasis added]

It seems that Adams received backlash, and his reaction here shows his frustration at the presumption that people would take one quotation out of context in light of the bulk of his work.

Adams’ chagrin at bolstering antiquity over constant improvement was also a sentiment that Jefferson shared. In an 1898 letter to William Munford, Jefferson censures those who consider established learning at its present limit. Though the second paragraph of his letter is dense, he stands his ground when he says that

"I join you therefore in branding as cowardly the idea that the human mind is incapable of further advances. this is precisely the doctrine which the present despots of the earth are inculcating, & their friends here re-echoing; & applying especially to religion & politics; ‘that it is not probable that any thing better will be discovered than what was known to our fathers.’ we are to look backwards then & not forwards for the improvement of science, & to find it amidst feudal barbarisms and the fires of Spital-fields. but thank heaven the American mind is already too much opened, to listen to these impostures; and while the art of printing is left to us science can never be retrograde; what is once acquired of real knowlege can never be lost.

Like Jefferson, I am thankful the American mind is open, but am concerned that ‘these impostures’ are easy to take at face value when whittled away from original context. Privileging Adams’ advice from a graduation speech over his words in the defense of the Constitution of the United States disregards his overarching philosophy. Though the real knowledge of his words exists in print, as Jefferson celebrates, the mass media uses the Adams’ patriotic authority to offer historical snippets without the cloth of their author’s beliefs.

In returning to the original quotation, now informed by the context of both Adams’ and Jefferson’s words, I find myself agreeing with them in the way I think they intended. The principles of education that I will pass to my posterity will be a deep understanding of language, a critical awareness of audience and context, and a persistent questioning of the effect of inclusion and omission. A curious mind, the skills to ask and answer questions about what came before you, and to build and follow your own quest into the future - those are the foundation of my own guiding principles.

Teaching Primary Sources Using EdCafes:

Questions:

- how did the American Forefathers approach improvement of oneself and society?

- what do primary sources look like on the internet, and how do you evaluate their legitimacy?

- how does punctuation and editing affect the meaning of a text?

Intro/Hook:

Key Vocab - hazard - risk, posterity - future generations

Give students the core quotation and have each read it to the other. With a partner, rewrite it in the form of a haiku, tweet, or 10-word sentence.

Rationale: in reading it out loud, each student hears the language of the sentence twice. Longer sentences have their rhythm that students find easier when listening, and it gives practice at parsing together their relationships.

or

Cut the core quotation into phrases, and have partners attempt to put it together.

Rationale: through puzzling through how to arrange the sentence, students practice phrasing and pay attention to ‘who is doing what.’

Lesson:

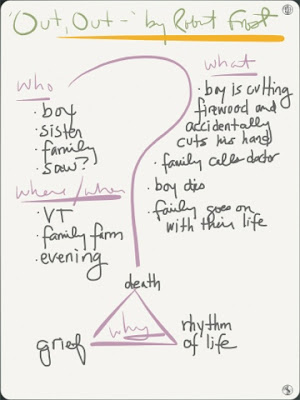

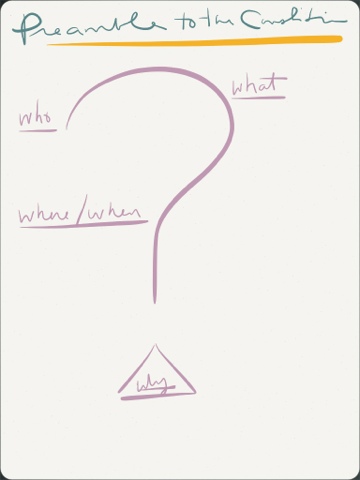

Each corner of the EdCafe will have four related documents to study. Each document relates to the quotation we started class with, but they span from 1798 to present day, so you’ll have to dig into each of the sources to get a grasp on them. Be patient with the language and read it out loud - each group has multiple dictionaries for a reason - use them to help you in your quest. Practice your questioning techniques - have someone in the group be a Question Scribe and write down all the questions the group asks. You’ll have a good amount of class to work on this, so don’t be intimidated by the length of the sentences or the large paragraphs.

Each of the four questions asks you to read the texts, move up a level and understand how they fit together, and then synthesize what you have learned. Pay close attention to what each question asks. The question you choose will be your prompt for your writing tonight.

Recommended:

1) Encourage students establishing a ‘plan of attack’ when they get in the groups (break down what the question is asking them to do)

2) Encourage students to read the text out loud

3) Have each group choose a Question Scribe to record as many questions as possible, perhaps on a projected Google Doc

If possible, give each student all four texts, either on paper or via technology.

| Corner 1 | Corner 2 | Corner 3 | Corner 4 |

| Describe Adams’ original audience. How was his quotation reacted to over time? How would Adams react to Constitution.org’s text of his words? | Constitution.org’s url shows that their text is considered a primary source. You are the judge - should this be used as a primary source in a research paper? On what basis do you rest your judgement? | What would Jefferson say about Constitution.org’s text of Adams’ words? | Choose three of the texts, create a Path to Purpose for each and craft Seven Steps to a Thesis** |

Walk around and check in on the groups. Focus on the group facilitators, each student having whatever you require for notetaking, always coming back to the question.

Closure:

Give each student a notecard (if you’re fancy, have different colors for each corner). Have students form groups of at least one member from each corner and share what they’re going to be writing about that evening. Have them write their thesis / topic on that notecard and collect before the end of class.

Resources:

Bundlenut of links to the four sources and original quotation -

bit.ly/AdamsEdCafeBundlenut

Common Core Standards

Reading Standards for Informational Text - Grades 11-12 Students:

Key Ideas and Details

1. Cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inference drawn from the text, including where the text leaves matters uncertain.

2. Determine two or more central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text

3. Analyze a complex set of ideas or sequence of events and explain how specific individual ideas, or events interact and develop.

Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

7. Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in different media or formats as well as in words in order to address a question or solve a problem.

Questions? Comments? Suggestions? Comment here or tweet to @katrinakennett